Why It Took Me 17 Years and Deirdre’s Other Questions

It was well past our turnaround time. Or, it would have been, if we’d had enough sense and experience to HAVE a turnaround time. We were 2500 feet below the summit of Mount Whitney, just beginning the climb up the couloir. Actually, to the left of the couloir - since the couloir itself was full of snow. We were already scrambling with our hands on this precipitous pitch. Our upward progress was infinitesimal. This was insanity - but which one of us was going to call it quits? We kept going. That is, until the first drops of rain started to fall. We looked at each other and, without discussion, we knew - it was time to turn around.

It was early August, 2005. I don’t remember how the plan evolved, but I’m sure I’d expressed to my husband Tad at some point that I’d like to summit Mount Whitney. Several years before that, before Tad & I started dating, he had submitted Whitney with his friend Mark. The two of them had ascended Mount Whitney via the Mountaineer’s Route. At 14,505 feet, Whitney is the highest mountain in the lower-48. There are two primary routes to the summit from the east side: the main Whitney Trail, and the MR. Both routes start at Whitney Portal, at 8400 feet, so they both ascend roughly 6000 feet. The difference is that the main trail is about eleven miles one-way, and the MR is about four. Six thousand feet gain in four miles! And the last 2000 feet to the summit are ascended in the final half mile. Horizontal distance is meaningless on the MR.

Both Tad and Mark had been active on a caving-focused search-and-rescue team, which involved a lot of technical climbing. That, plus being young men in their late-20s, made lots of things seem easier than they really were. Fast forward to 2005, when I expressed interest in this hike, Tad immediately said, let’s do the MR – why hike all those twenty-some miles round trip when you can just do it in eight? Yes, why indeed!

We assembled an intrepid group of five of us who decided to tackle the climb. I did a bit of training, including summiting White Mountain, another fourteener with a much easier hike to its summit; but I was young, and in tip-top shape as an avid triathlete at the time. Fitness would not be the issue. Our plan was the traditional one for this route: day one we’d hike to Upper Boyscout Lake and set up camp. On day two, we’d start early, hike past Iceberg Lake, summit (easy peasy!), and then hike back to our camp. Day three we’d head back down the mountain.

The hike starts out pretty mellow – the first ¾ mile shares the main trail. But as soon as you turn off the main trail, it gets steep. We made slow work across the Ledges (more on that later); and late in the afternoon, when we finally rolled into Lower Boyscout Lake, one of our group was really feeling the altitude. We modified our plan, and decided to camp among the mosquito-infested trees at LBS (setback #1).

The next morning, not feeling much better, two of our group decided to turn around. Tad was not feeling great either – he may have been up for it in his SAR days while in his late-20s, but it’s funny how time catches up with you. The two of us remaining were feeling fine, and wanted to push on – but remember that this was 2005. No one had a GPS or means of communication. Tad was our navigator. With rough directions from him, a paper map, and maybe a compass (did we have a compass? I am not sure), we headed up without Tad (setback #2). We started out ok, but eventually got pretty lost somewhere south of UBS (setback #3). Finally we arrived at Iceberg Lake and took a good look at the couloir we were now supposed to ascend. It had been a very high snow year, and in early August, the couloir was still full of snow (setback #4). We started up as best we could until the raindrops started to fall. A sense of self-preservation finally hit us and we turned back.

I don’t remember much of the hike down. I know we spent our second night at LBS when we met back up with Tad, and with such a short descent on day three, we got back to the Portal pretty early. The hubcap-sized pancakes served at the store were amazing.

This hike stayed with me. Years passed: I had children, I stopped doing triathlons, I worked a lot. Shortly after our failed summit attempt – which in hindsight I view as more of a success that we did not manage to kill ourselves, rather than a failure that we did not summit – one of our group hired a guide to get her to the top, and a seed was planted. In 2016, I took the Sierra Club Wilderness Basics Class and started trying to figure out how to get out more, get back to the mountains and backpacking and all that fun stuff. I had a bit of a setback (Project Perky) but finally was able to put a date on the calendar: I’d hire a guide and summit via the MR in 2019.

I had some friends who were game, and we spent the summer leading up to our hike getting trained up. It was so much fun tackling some classic peaks in Southern California that I’d never done before: San Bernardino; Mount Baldy; MSJ via Deer Springs. I felt ready, but I was still nervous. I knew first hand how tough this hike would be, and I was starting to suspect that our group of five were at such different levels of experience and hiking paces that even with a guide this might be a tall order.

The story of the 2019 failed attempt is a lot less interesting than our 2005 epic mistake factory. Suffice it to say that we were just not a good mix of skills. We did everything right: plenty of training; all the right gear; hired some great guides; got to Whitney Portal the night before to acclimate. But we were just too slow. We did make it to UBS Lake on day one per the plan, but it took us over eight hours to get there. We got a late start on day two. All five of us (plus two guides) started up the couloir, but after a short time two of our party (plus one guide) turned back. I think we made it maybe halfway up the couloir when Trevor, our guide, said, guys, I don’t think it’s going to happen.

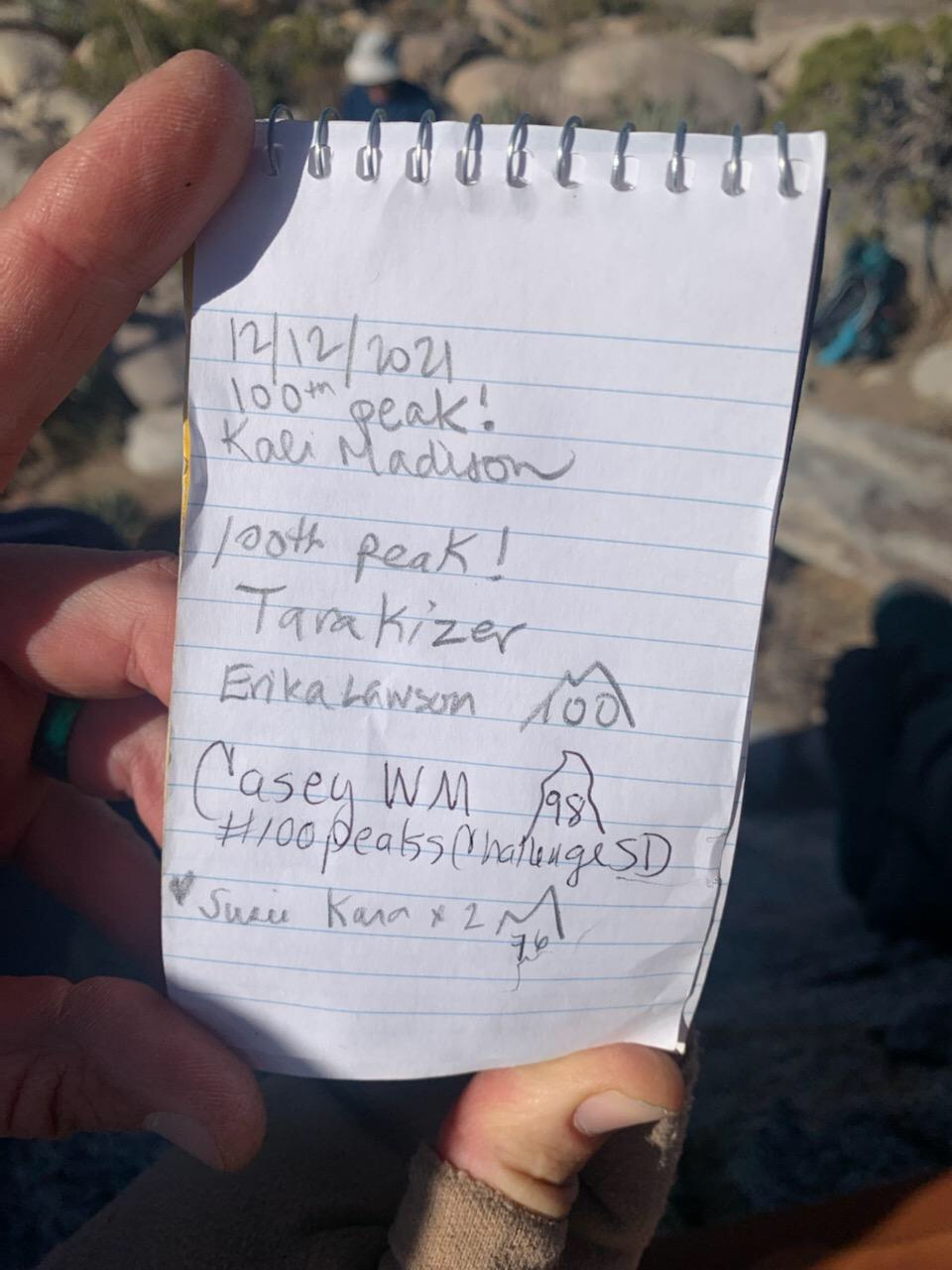

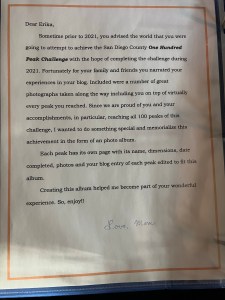

Time for a new plan. In the years since 2019, I have unquestionably hit my goal of becoming an “avid hiker.” I now have a small but mighty group of pals who I call my hiking companions. In 2020 I hiked the John Muir Trail, which included summiting Mount Whitney from the west side. The JMT terminates at the summit of Whitney, joining the main Whitney trail coming up from the Portal about 1000 feet below the summit. We got there in time for sunrise, and it was stunning. In 2021 my hiking buddies and I completed the San Diego 100 Peaks Challenge, which improved my skills significantly in terms of climbing steep terrain on loose scree – maybe not at altitude, but still a translatable skill. I did a few more big hikes in the Sierra Nevada, including Red’s Meadow to Happy Isles, and earlier this year, joining my friends for a couple of days along their JMT route via the Rae Lakes Loop to resupply them. I was ready!

I’d signed up with the same guide service, Sierra Mountaineering International, and was assigned Trevor, the same guide as in 2019! I asked Kali to join me. I realized that for me to summit this difficult climb, I would need to be the slowest hiker on the team. I could not be pulling anyone along; I needed everyone else to be pulling me along. Neither of my two previous failures were due to my own lack of ability – or at least I had not had the opportunity to truly test myself. Kali and I have comparable hiking paces, and she is a stronger climber than I am. On top of that, she is also fifteen years my junior – so that helps.

I’d also planned an extra day of acclimation, and on the Saturday after Labor Day, Kali & I headed up to Horseshoe Meadows, a walk-up campground at 10,000 feet just south of Whitney Portal. The forecast called for rain that night – and it sure did rain – but for it to clear up by Monday. Our plan was to do an easy backpack to Cottonwood Lakes on Saturday, then on Sunday, drive in to Lone Pine for lunch, then make our way up to a reserved campsite at Whitney Portal. On Sunday morning, as we descended back into cell phone coverage, my texts started to arrive… including one from the guide service. Now, they are used to bad weather up here, and as a result, they almost never cancel due to weather – they strongly recommend purchasing trip insurance for this very reason. But the weather forecast on Monday had changed, and was now looking so awful that even Trevor did not want to climb that day. He offered to let us reschedule. We stopped at the Alabama Hills Café for lunch to ponder our options. With resignation and disappointment, we hit the road toward home. What else is this mountain going to throw in my way!!??

But I did not have to wait long. The weather this whole year has been unusual, so I decided to reschedule ASAP before things got worse. My job is fairly flexible, but unfortunately, Kali’s is not. So when an opportunity came to grab a slot two weeks later, I jumped at it – even though it meant going without Kali. It was a hard decision but I really wanted to get this thing done. I was trained, I had the time. I decided to go.

So, early last Saturday morning, I hit the road – again – this time by myself at the wheel of our trusty old minivan. I was giving myself one less day of acclimation, but it would have to do. I arrived in Lone Pine at around 10am and stopped by Big Willi’s to buy a Slog Queen hat, but they were sold out. I lingered in town a little bit – love that place – and got a turkey and avocado wrap to go from the Alabama Hills Café. Arrived at Horseshoe Meadows again around noon. It was surprisingly uncrowded, and the weather was beautiful – such a contrast to two weeks ago. I set up my tent and enjoyed my wrap at the picnic table. In the afternoon I did an easy six mile hike, fashioning a loop up and over Mulkey Pass, southwest for a bit on the PCT, then back down via Trail Pass. The next morning my tent was coated in frost.

Sunday morning worked like clockwork. I drove to Whitney Portal, parked in the overflow lot, placed a small bag with food and scented items, along with a note indicating when I’d return, into the bear locker. The rest of my few non-hiking items I stashed in a duffel bag tucked away in the back of my otherwise empty minivan and covered it with a towel (bears are smart). Walked up to the store, and chatted with Doug while waiting for Trevor to arrive.

As this was my third time on (most of) this trail, I had it chunked in sections in my head. The first part was the only easy bit along the main trail. We covered this in no time. The turnoff for the MR is unsigned, just before the main trail crosses Lone Pine Creek. The steepness of the climb begins immediately. This section goes through a damp forest and itself crosses Lone Pine Creek twice – it reminds me very slightly of the wooded part of the Mount Baldy Ski Hut trail (just before the saddle), minus all the water and plus a few boulders scrambles.

Now you arrive at the first real challenge: the Ebersbacher Ledges, or E-Ledges, or, on trail, just “the Ledges.” The Ledges have no technically challenging bits, just a little bit of bouldering here and there; what makes this section notable is the exposure. The route hugs a sheer cliff wall on one side, and a dropoff on the other. I was glad to put the Ledges behind me, at least until two days from now when we’d have to come back down.

The next section is from the Ledges to LBS Lake, which is straightforward if a bit rocky. All three times I’ve done it now this is the section with the most flowers and the prettiest views – you can look up and see much of what you have yet to hike. At this point Trevor was commenting on what a great pace we were setting – I think he was prepared for something much slower given our 2019 experience. We stopped at the LBS Lake outlet for a snack.

From here there are two more sections before reaching UBS. First there is some pure bouldering as you climb up beyond LBS. The “trail” here offers plenty of choose-your-own-adventure opportunities. Next, the route opens up onto “the Slabs”: sheer expanses of granite with rivulets of Lone Pine Creek flowing down. This is my favorite section of the trail, with nothing separating you from the water but a few feet of stone. It’s a calf-burner on the way up, and a quad-shredder on the way down. Nearly above tree-line at this point, the landscape here at 11,000 feet becomes classic Sierra, with gravel footing, streams everywhere, and scrubby vegetation that I wish I knew the names of.

We arrived at UBS Lake at 12:30pm, in exactly four hours – less than half the time it took in 2019! I hate getting to camp early, and this is where having more hiking companions would have been nice (although Trevor was good company). I took a nap, enjoyed the scenery, and searched the stream for fish – plenty of them in the UBS outflow. On this trip I brought my backpacking watercolor kit, which kept me occupied. I could not watch anything on my iPhone – my downloads had failed, of course (my luck) – but that was probably for the best. Our campground had a direct line-of-sight to Lone Pine; if I stood in just the right place I could get four bars of coverage.

We held out until 6pm when Trevor made a ridiculously good dinner of gnocchi, chicken, and chickpeas in alfredo sauce. No cold soaking this trip! The sky exploded in color as the sun set. I crawled into my tent at 7pm and was fast asleep by 7:30.

Monday morning arrived – today was the big day. There was another group camped nearby and they hit the trail (not very quietly) under headlamps around 5 or 6am. Trevor was confident enough in my speed that he did not feel like we needed an alpine start; we aimed for 7am and actually hit the trail at 6:45. The hike from UBS to Iceberg was another 1000 feet of rocky, alpine ascent; but we covered it with our light daypacks in an hour – getting passed once by some young bucks who were headed up to free solo the East Buttress. Upon arriving at Iceberg, my nerves were peaking – I’d gotten this far twice before!

Setting our trekking poles aside, so began the ascent. The scramble up the couloir is a mix of steep sliding scree steps, with a little bouldering here and there. Sometimes the scree turns to rocky talus – always slippery. As I was “hiking” (if you can call it that), I tried to think of what to compare it to. It was a bit like Indianhead, or the last pitch up to Mile High Peak from Rattlesnake Canyon. On one hand, I didn’t feel like the slope was trying to kill me – no stabby plants! But on the other hand, this just kept going, and getting steeper. Also, eventually we arrived at some patchy snow – sure isn’t any of that on Indianhead! It was old, crusted, and not very slippery; but still disconcerting to have to put both feet on it, no hand-holds, on a steep incline. At one point there was a tricky rock climbing move that made me feel a little exposed, and I did not like that – it was fine, but exposure is an exhausting mental game. My main limitation was neither the footing nor the technicality – it was my ability to breathe. I was fairly acclimated at this point, and I’d been taking Diamox for several days by now. I had done a lot of “zone 2” base training just for this climb, and I could tell that it was paying off. But still – need … to … breathe … !!! Climbing at 14,000 feet elevation is no joke.

We finally topped out at the Notch – the top of the couloir and the base of the Chute. I must say I felt pretty proud of myself to have caught up with our neighbors at this point, despite them starting at least an hour before we did. They were in the process of roping up for the Chute – a woman, two men, and a guide. Trevor and I stopped for a snack break and to give them a head start, and just then, Kurt, the owner of SMI, arrived with his two clients who were climbing MR in one day. They had started at Whitney Portal at o’dark-thirty in the morning and were making great time.

The Chute is the steepest and most technical part of the entire climb, 400 feet below the summit. Trevor showed me that the initial reach to get onto the rock face would be the hardest of the climb, and if I could handle that I’d be fine. We opted not to bother with the rope which would only get in the way and slow us down. Up we went, soon overtaking the party of four. The Chute took us literally only about twenty minutes … and it was SO MUCH FUN!! Yes, there was exposure, but it was all behind me (literally) – I just kept my eyes up and ahead. The actual rock climbing was easy with only a few tricky spots. Then, all of a sudden, we were done!

I MADE IT!!! Finally, after seventeen freakin’ years, I had vanquished the Mountaineer’s Route; bucket list checked off; business now finished. The summit itself was almost irrelevant – it was 11am and the crowds had arrived; besides, I’d been there before. This had been all about the journey, not the destination. We lingered a bit, taking photos and exploring the hut*. But as they say: going up is optional; going down is mandatory. It was time to start the slog down. Seems easy, but honestly going downhill on that scree shit can be so much worse than going up!

Trevor took me westward off the summit to “the traverse” because I’d been whining about downclimbing the Chute – climbing up on rocks is fun; climbing down is scary. Of course the traverse was just a longer segment of scree, so I’m not sure if it was really any better. We took a little break at the Notch and then the real work of going down the couloir began. It was fine, just tedious. I tended to slide on my butt a lot more than Trevor did (in fact I did not see him do that even once) which means I was scraping a lot of the rocks off with me – no points for style.

Finally at Iceberg Lake I felt like I could mentally relax. The hardest of the hard work was done. Descending down the rest of the steep trail would be hard, but only physically. The adrenaline could finally start to dissipate. We stopped for lunch and to hydrate, and then kept moving. We were back at camp by 2:45pm – an eight hour day, exactly.

I guess my story mostly ends here. We lazed away the afternoon, watching the clouds roll in, sometimes raining on us. We snacked and had hot drinks. Trevor spoiled me again with a rich dinner of chicken, tortellini, and pesto sauce. I ate so much I had no room for dessert. Took a lot longer to fall asleep – lingering adrenaline is more powerful than an after-dinner espresso. My air mattress had sprung a slow leak and I had to refill it about every hour – so that was fun. And it was warm! I would have preferred my lighter sleeping bag for sure.

The next day we had a lazy morning and got going around 8:30am. Our neighbors had started about 45 minutes prior, and we easily caught up with them at LBS. For the first time we chatted – turns out it was a 57-year-old badass mom and her two grown sons! Put me in my place about feeling all smug when we’d passed them – good for her! The Ledges presented one final mental challenge. From there we took no more breaks. At the main trail we turned right instead of left – Trevor led me down the “Old Whitney Trail,” dizzy with switchbacks down to the backside of the Portal. An early lunch of a delicious cheeseburger and beer was inhaled. I took my time – I’d hit traffic going home no matter what, so might as well linger. The thing is done.

*I said I would answer all of Deirdre’s questions, so, about the hut. No, you cannot legally sleep in it, although I have heard of people who have done so. It is divided in half and one half is locked up. The other half is open and full of Sharpie graffiti. Apparently it is VERY VERY BAD to be there during a lightning storm. More about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smithsonian_Institution_Shelter. Also, no I did not carry that metal sign. There is currently a (broken) wooden one there too. These signs are made and carried up by other hikers. Many in the hiking community think they are trash and not “LNT.” The NPS apparently will remove them on occasion.

And a coda: While I inhaled my cheeseburger at the Whitney Portal Store, doing my best not to swallow any bees, I got to meet Crazy Jack Northam. Jack, a 75-year-old San Diegan, has climbed Mount Whitney 205 times as of our meeting. He told us with great fanboy excitement the story of the time he was helping another hiker who turned out to have been on three seasons of Survivor.